Detoning Direct/Indirect Syscalls by several approachs

Here, we’ll demonstrate how to detect both direct and indirect syscalls by discussing detection rules using Elastic, YARA, and dedicated code. We’ll cover several approaches, including Static Analysis, Page Guard + VEH, Call Stack inspection, and ETW-TI.

In this blog post, we’ll focus on the topic of direct/indirect syscall. I won’t go into detail about how a syscall works or the hooking mechanism. If you’re not familiar with the topic, you can check out my previous posts on hooking and direct syscall.

This technique, for quite some time, has been (and still is) capable of executing APIs in a stealthy manner against some EDRs that rely on userland hooking, often allowing them to be bypassed.

Here, I’ll share my perspective on how this can be detected, present several alternatives, and highlight some of its weaknesses. We’ll discuss it from a static analysis point of view, as well as InstrumentationCallback, Guard Page + VEH, Call Stack, and ETW-TI.

Static

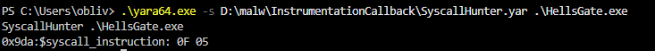

The simplest method would be to search for the syscall instruction within the analyzed code using YARA. Here’s an example rule:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

rule SyscallHunter {

meta:

description = "Detecting syscall instruction in code"

author = "@ Oblivion"

date = "2025-04-02"

reference = "https://oblivion-malware.xyz/posts/detecting-syscalls"

strings:

$syscall_instruction = { 0F 05 }

condition:

any of ( $syscall_instruction* )

}

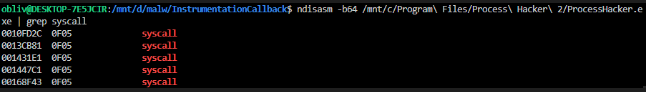

Result when using it on a sample that implements HellsGate:

This could be bypassed by the attacker obfuscating the instruction, deobfuscating it at runtime, executing it, and then obfuscating it again. However, this approach is not commonly used. In most cases, the rule alone would already be sufficient for detection. Still, a defender could mitigate this technique, although it would require some effort. Another point is that this could lead to many false positives, since it’s not an uncommon byte sequence.

For static analysis, it’s more effective to use a disassembler and then perform a “grep” for the syscall instruction, as demonstrated below:

InstrumentationCallback

We can configure the return address of the syscall to wherever we want and determine where it’s being invoked from. If it originates from a memory region belonging to a DLL like win32u, ntdll, or others, it’s typically considered non-malicious. Otherwise, it’s flagged as malicious. We can also analyze its parameters to better understand what’s happening, along with the full call stack. Below is an example of how to enable/configure this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

LONG Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

HANDLE ProcessHandle = ::GetCurrentProcess();

PROCESS_INSTRUMENTATION_CALLBACK_INFORMATION InstCallbackInfo = { 0 };

InstCallbackInfo.Callback = CallbackFunction;

InstCallbackInfo.Reserved = 0;

InstCallbackInfo.Version = 0;

Status = ::NtSetInformationProcess(

ProcessHandle, (PROCESS_INFORMATION_CLASS)ProcessInstrumentationCallback,

(PVOID)&InstCallbackInfo, sizeof( InstCallbackInfo )

);

if ( Status != STATUS_SUCCESS ) return;

One option for the attacker is to use the same approach but pass NULL in InstCallbackInfo.Callback = CallbackFunction;. We have an example of this behavior with SentinelOne EDR—it sets an InstrumentationCallback in addition to hooking certain functions. I’ll demonstrate when and how this happens in its implementation. First, we have the following code snippet running in x64dbg on a machine with SentinelOne installed:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

auto WINAPI WinMain(

_In_ HINSTANCE Instance,

_In_ HINSTANCE PrevInstance,

_In_ PCHAR CommandLine,

_In_ INT ShowCmd

) -> INT {

NTSTATUS NTAPI ( *NtSetInformationProcess )( _In_ HANDLE ProcessHandle, _In_ PROCESS_INFORMATION_CLASS ProcessInformationClass, _In_ PVOID ProcessInformation, _In_ ULONG ProcessInformationLength );

NtSetInformationProcess = ( decltype( NtSetInformationProcess ) )::GetProcAddress( ::GetModuleHandleA( "ntdll.dll" ), "NtSetInformationProcess" );

LONG Status = STATUS_SUCCESS;

HANDLE ProcessHandle = ::GetCurrentProcess();

PROCESS_INSTRUMENTATION_CALLBACK_INFORMATION InstCallbackInfo = { 0 };

InstCallbackInfo.Callback = NULL;

InstCallbackInfo.Reserved = 0;

InstCallbackInfo.Version = 0;

::VirtualAlloc( 0, 1000, 0x3000, 0x40 );

Status = ::NtSetInformationProcess(

ProcessHandle, (PROCESS_INFORMATION_CLASS)ProcessInstrumentationCallback,

(PVOID)&InstCallbackInfo, sizeof( InstCallbackInfo )

);

if ( Status != STATUS_SUCCESS ) return;

::VirtualAlloc( 0, 1000, 0x3000, 0x40 );

}

I overwrite the callback, effectively removing the one previously added by SentinelOne. Before doing that, I use kernel32!VirtualAlloc just to demonstrate its execution with the callback still active. Then, I call kernel32!VirtualAlloc again after removing the callback to show that it’s no longer in effect. Below is a demonstration video:

As we can see, we’re able to remove it without any issues—even though the ntdll!NtSetInformationProcess API is hooked. For some reason, SentinelOne allows its callback to be removed right under its nose.

Call Stack

An approach I find quite effective is call stack analysis—Elastic EDR has been focusing on this method for quite some time. You can find a great write-up here. It’s very efficient for detecting shellcode execution in memory, especially when paying close attention to unbacked private memory regions with execution permissions being used by certain APIs.

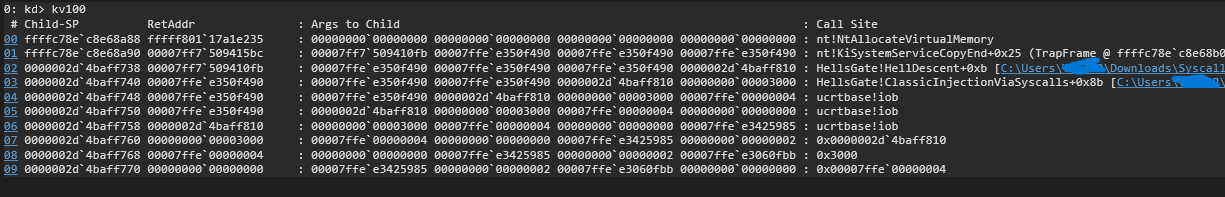

For detecting direct syscalls, our main focus should be on the return address—specifically checking whether the caller into the kernel originates from a legitimate DLL such as ntdll, win32u, or others that contain syscall stubs, rather than from an executable. See the example below:

Above, we can see an execution of ntdll!NtAllocateVirtualMemory coming directly from the “HellsGate” executable, rather than through a Microsoft DLL as would normally be expected. This is already a strong indicator of direct syscall execution.

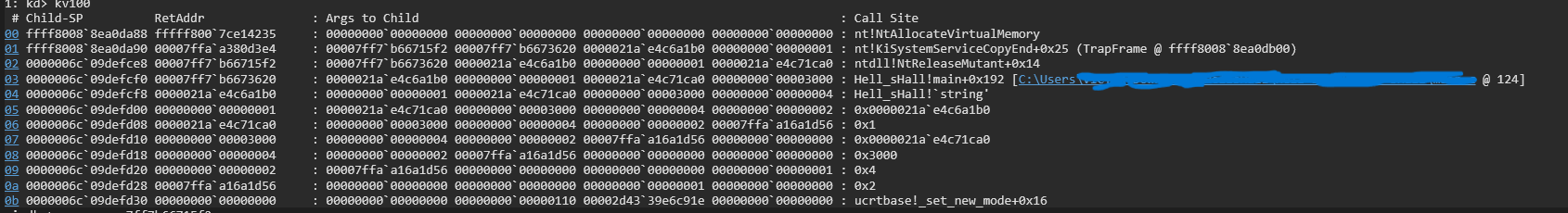

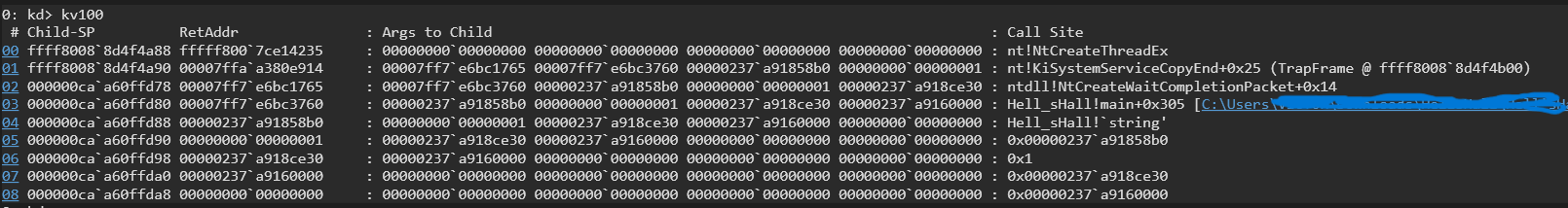

Now let’s take a look at an indirect syscall, paying closer attention to API “spoofing.” What happens in some approaches is that the attacker sets the SSN (System Service Number) of the desired function and then performs a jmp into the memory space of another API, jumping directly to the syscall instruction. When this is done, we get a call stack like the following:

ntdll!NtAllocateVirtualMemory

ntdll!NtCreateThreadEx

As we can observe, it’s quite easy to identify that API spoofing is happening—because in the case of ntdll!NtCreateWaitCompletionPacket, we actually see ntdll!NtAllocateVirtualMemory being executed in the kernel. This mismatch is a clear indicator of spoofing.

Elastic have the the great rule for direct syscalls, you can see rule here

Page Guard + VEH

We implemented a hooking technique that differs from the conventional method, which usually involves overwriting the API with an unconditional jump (jmp). In our case, we add a vectored exception handler (VEH) and force an exception at the point where we want the hook to be triggered.

When the function is invoked and the exception is raised, we inspect the origin of the exception:

- If it originated from the base address of the function, we can treat it as a legitimate syscall.

- If the exception is triggered at the

syscallinstruction, we know there was a jump directly to that instruction, bypassing the routine responsible for setting up the syscall number (SSN).

To start, we change the memory protection of the functions we want to hook to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ | PAGE_GUARD.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

auto Instance::SetGuardPageProt(

_In_ PVOID Address,

_In_ ULONG Size

) -> BOOL {

ULONG OldProt = 0;

return ::VirtualProtect( Address, Size, PAGE_EXECUTE_READ | PAGE_GUARD, &OldProt );

}

We’ll create a structure and instantiate it globally.

1

2

3

4

5

6

typedef struct {

PVOID FuncPtr;

PCHAR FuncName;

} HOOK, *PHOOK;

HOOK HookMgmt[FN_C] = { 0 };

Next, we’ll set the value of FuncName and loop through to retrieve the function’s address, changing its memory protection accordingly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

HookMgmt[0].FuncName = {FUNC_OF_YOUR_CHOICE};

HookMgmt[1].FuncName = {FUNC_OF_YOUR_CHOICE};

HookMgmt[2].FuncName = {FUNC_OF_YOUR_CHOICE};

HookMgmt[3].FuncName = {FUNC_OF_YOUR_CHOICE};

HookMgmt[4].FuncName = {FUNC_OF_YOUR_CHOICE};

for ( INT i = 0; i < sizeof( HookMgmt ); i++ ) {

HookMgmt[i].FuncPtr = (PVOID)::GetProcAddress( (HMODULE)NtdllPtr, HookMgmt[i].FuncName );

}

for ( INT i = 0; i < sizeof( HookMgmt ); i++ ) {

if ( !( Instance::SetGuardPageProt( HookMgmt[i].FuncPtr, SYS_STUB_LENGTH ) ) ) {

mPrint( "error changing hook functions memory protection to page guard" ); return ::GetLastError();

}

mPrint( "# %d set page guard protection to %s at %p", i, HookMgmt[i].FuncName, HookMgmt[i].FuncPtr );

}

In our exception handling function, it will look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

auto DetourFunction(

_In_ PEXCEPTION_POINTERS e

) -> LONG {

mPrint( "inside of exception handler" );

if ( e->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionCode == EXCEPTION_GUARD_PAGE ) {

if ( !( memcmp( e->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress, &SyscallOpcode, sizeof( SyscallOpcode ) ) ) ) {

mPrint( "potential indirect syscall jumping to instruction at %p", e->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress );

} else {

mPrint( "legitimate access at %p", e->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionAddress );

}

}

return EXCEPTION_CONTINUE_EXECUTION;

}

As I mentioned above, check if expcetion address == syscall instruction, thus knowing if a direct jmp was executed for that.

Note: This implementation is very simple and needs some adjustments to work properly, the code above is more for a demonstration of how it would be.

ETW-TI + Kernel Callbacks

Summarize: it’s a mechanism that logs events from within the kernel, which makes it significantly harder to bypass—unlike standard ETW, which operates in userland and runs within ntdll.dll.

ETW-TI provides various keywords that we can use as a secure form of telemetry. Unlike userland solutions like hooking, this method offers more reliable and tamper-resistant visibility. Here’s a list of the two keyword sets: https://github.com/jdu2600/Windows10EtwEvents/blob/main/manifest/Microsoft-Windows-Threat-Intelligence.tsv.

With these, we’re able to monitor actions such as memory allocation (local/remote), memory protection changes (local/remote), virtual memory writing (local/remote), and other behaviors listed in the linked manifest.

We also gain access to other valuable kernel-level events, such as:

- Process creation via

PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine - Thread creation via

PsSetCreateThreadNotifyRoutine - Image loading via

PsSetLoadNotifyRoutine - Monitoring of handle operations like

DuplicateHandle,OpenProcess, andOpenThreadviaObRegisterCallbacks.

So even if we can bypass userland from some hook we would still be able to know what is being done based on ETW-TI and Kernel Callbacks.

Epilogue

Here, we’ve covered several approaches from a detection standpoint, and I hope it’s clear how powerful the combination of these techniques can be.